Experiencing Japan's Four Seasons Through Its Biggest Celebrations

Tanabata 七夕 - around July 7th

Tanabata, a captivating festival in Japan, has its roots in China's Qixi Festival and was introduced to Japan during the Nara period (710 to 794). It commemorates the annual meeting of Orihime and Hikoboshi, represented by the stars Vega and Altair, lovers separated by the vast Milky Way. Their celestial reunion occurs only once a year, on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, typically in July or August in the Gregorian calendar. The festival is celebrated on various dates, primarily on the seventh day of the seventh month or around that time. Originally, Tanabata was closely tied to the old lunar calendar, and had strong connections with the Bon Festival, occurring around the 15th day of the seventh month in the old calendar. However, with the adoption of the Gregorian calendar in the Meiji era, the Bon Festival moved to around the 15th day of the eighth month, leading to a gradual disassociation between the two festivals.

A prevalent tradition during Tanabata involves writing wishes on colorful strips of paper called Tanzaku (短冊) and hanging them on bamboo branches. This unique practice, dating back to the Edo period, primarily revolves around wishing for improvement in artistic and handcrafting skills. The wishes written on Tanzaku often pertain to arts and crafts. Traditionally, these bamboo decorations are displayed on July 6th, and in coastal regions, they are set adrift in the sea during the early morning of July 7th. Some areas choose to place these decorations on bridges crossing rivers. Local customs may vary, from taking a break from farm work to incorporating rain rituals or mosquito-sending ceremonies.

Modern Tanabata festivals predominantly feature daytime activities and evening fireworks, with less emphasis on the traditional or religious aspects of Tanabata. These festivals can differ by region but often include contests for the best Tanabata decorations, parades, food stalls, carnival games, creating a lively and festive atmosphere.

Doyō no Ushi no Hi 土用どようの丑 - between July 19th and August 7th

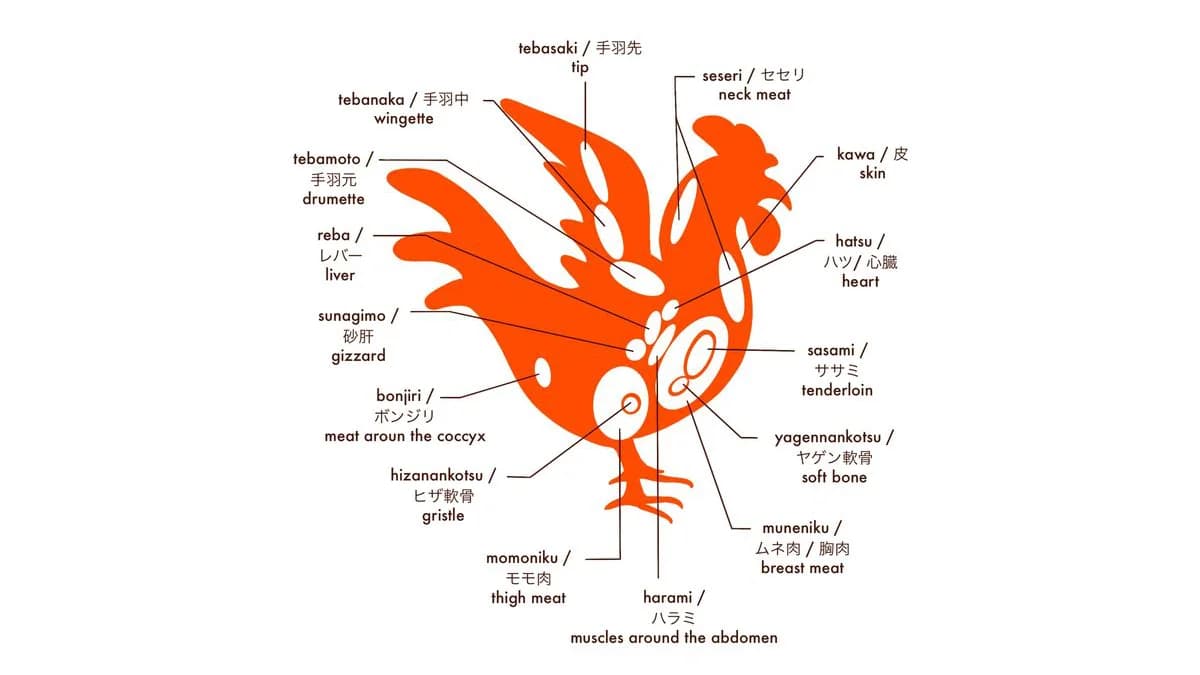

Doyō no Ushi no Hi is a traditional Japanese event associated with eating eel. It occurs during the hottest days of summer and is based on the Chinese zodiac calendar. The term can be broken down as follows:

"土用" (Doyō) refers to the Doyō period, which is believed to be a time when the heat and humidity are at their peak during the summer; "丑" (Ushi) represents the zodiac sign of the Ox, it's the second animal in the Chinese zodiac cycle; "日" (Hi) means "day”.

During Doyō no Ushi no Hi, it is customary for people to eat grilled or boiled eel, believed to provide stamina and protection from summer fatigue and illness due to its nutritious qualities.

It's celebrated on various dates between July 19th and August 7th, with the most popular date being July 29th, which is considered the peak of the summer heat. This tradition is widespread in Japan, and you'll find many eel restaurants offering special dishes during this time.

Obon お盆 - around July 13 - 16 and August 13 - 16

Obon (お盆) is a centuries-old traditional Buddhist festival that holds great cultural significance. It is a time when families come together to honour and remember their ancestors' spirits, who are believed to return to the world of the living during this period.

People visit their ancestral graves to clean and decorate them, offer food and incense, and perform rituals. Bon Odori, traditional folk dances, are an integral part of the festivities. These dances vary by region but generally involve rhythmic movements to the beat of drums and other instruments.

Interestingly, Shinto also observes its own version of Obon. In Shinto, Obon not only signifies the return of ancestors but also celebrates health and longevity.

As Obon approaches, there is a period referred to as “Shichinichi-bon” (七日盆), during which people prepare for Obon by cleaning graves, household altars, and ancestral shrines. During the Obon period, Shinto priests perform rituals and offer prayers.

While lanterns are occasionally used, in Shinto, it is customary to primarily employ white wooden lanterns for these purposes.

Floating lanterns are also used; they are set adrift on rivers and seas to guide the spirits back to the afterlife. Bonfires are ignited on hills or along riverbanks, illuminating the night as a beacon for the ancestors' return.

Last Updated: